Staying to Look

My name is Juli Brigo, I’m an Argentinian photographer, currently living in Los Angeles.

Over the past twelve years, I’ve lived in Iran, Egypt, Pakistan, and Algeria with my family due to my partner’s work. During that time, we traveled to 36 countries. This allowed me to explore not only major cities but also remote villages, deserts, mountains, and hidden corners of the world.

Each country left a mark. Some, like North Korea, Iran, and Algeria, were particularly complex to photograph, not just because of physical restrictions, but also cultural and language barriers. Still, being so close to these rarely-seen places, I made the most of every opportunity to photograph them, always with an attentive eye and quiet curiosity.

My fascination with photography began when I was a child. My father, also a photographer, gave me a little Olympus pocket camera when I was eight. At his house, he had a darkroom, and I would spend hours watching images slowly appear through water and chemicals. Since then, I’ve never stopped taking photos. Photography, for me, is not just a way to look at the world, but a way of inhabiting it.

2. Iran – CanonG16

What compels me to lift the camera is often an internal, almost physical sensation, something I can’t let go unnoticed. I’m not after spectacular or posed shots. I don’t seek the immediate “wow.” I’m not drawn to tourist images. I’m drawn to the ordinary, the imperfect, the small moments that hold deep meaning. I love photos that leave questions lingering in the air, that hold mystery. These are the ones that move me most. With time and distance, I often notice details I missed in the moment.

Traveling has taught me to look with respect and humility. In many places, it’s not possible to pull out a camera, and sometimes, that silence holds as much value. Photography became a bridge between silence and story, and a way to witness what often goes unseen. Even without a photo, looking was already a way of remembering.

In the end, everything we hold dear becomes part of a shared memory, even if it’s not visible.

My understanding of documentary photography evolved over time, especially living in countries where freedom of expression is limited. There, I realized that photography is not only art, it’s a powerful tool for bearing witness. When words fall short, images become memory. It’s an act of resistance, a way to be present, to show what’s often hidden or ignored. The camera becomes a mirror, a bridge, a shield—and a question: What’s really happening here?

In some places I’ve lived, an image can be uncomfortable or even dangerous. That’s why photography goes beyond aesthetics, it’s a way of resisting erasure. In a world where images circulate faster than stories, and social media dominates visual content, the essence of documentary work often gets lost. We chase instant impact, but that’s only a fraction of the story. Documentary photography needs time, presence, and space. It’s not just about what we see, it’s about inviting others to look deeper and hold space for complexity, contradiction, and silence.

I work with various equipment, but I always travel with a small Canon G16 and my smartphone. I also use a Canon 5D with a 50mm f/1.8 and a 24-105mm lens. One of the tools I hold dearest is my analog camera. I use an Ilford Sprite 35-II for personal projects, daily. Film forces me to slow down, to choose more carefully. I also enjoy disposable cameras when I can find them—there’s something playful about them. The things about cameras is that isn’t always easy to travel with the family and huge cameras, sometimes I regret about not having an amazing one, but then I remember that in those places having a huge camera is not cool, you just can’t, you have to go unnoticed.

2. Egypt – Ilford Spritell

Shooting on film is not just about aesthetics. It’s about pace, reflection, and intention. It allows me to trust my intuition and embrace waiting.

On my last trip to Buenos Aires, I left my Canon EOS 3 and started looking for a new analog option here.

I lost cameras, rolls of film, and photos along the way, with every move.

Going back to film wasn’t about nostalgia—it was about resisting a world that moves too fast, where everything is instantly erased and replaced.

In many of the countries I lived in, finding film was nearly impossible. In Egypt, I found some, but in Iran, Pakistan, and Algeria, it didn’t exist. I’d bring rolls back from trips and develop them in Buenos Aires. I also bought expired rolls, which sometimes resulted in total failure. After several disappointments, I learned that, in certain situations, digital was more practical—small, discreet, and less likely to attract attention. That matters. So does portability, especially with a nomadic lifestyle.

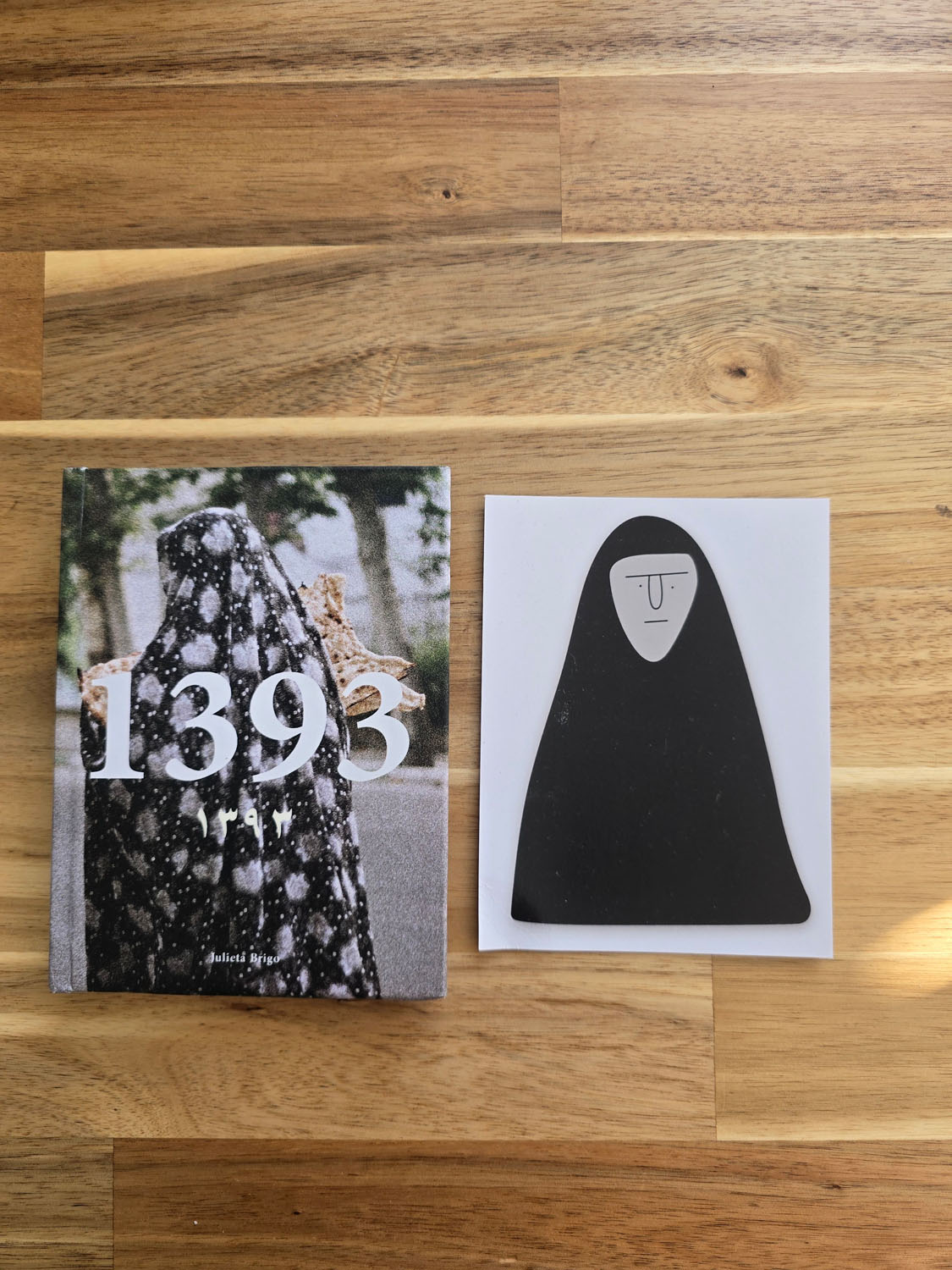

A few months ago, I published my first photo book in Argentina: “1393”. It took me ten years to feel ready to share those images. They weren’t conventional or “perfectly made,” and that made the process hard. My naturally messy nature made it even harder to select and edit. But one day, I knew it was time.

2. Pakistan

2. Iran – Canon EOS 3 . Reshot Canon G16

“1393 “is a deeply intimate book born in Iran, during one of the most transformative chapters of my life. The title refers to the Persian calendar—the year my family and I arrived in Tehran. From that point on, I began building a narrative that went beyond visual records. It’s about memory, observation, and inside storytelling. Through images that move between the everyday and the unseen, 1393 speaks to what can’t always be said, to what lives in silence, to what lingers at the margins.

Many of the photos were taken under challenging conditions, and they speak to a culture often misunderstood from the outside. The book is available in Buenos Aires and Los Angeles, at Ojalá.la, and also at independent photobook fairs in Argentina. I still develop all my film at the labs I’ve used for years—one in Buenos Aires, and a new one I love here in L.A.

Throughout the years, I’ve learned that photography is not just about capturing what’s in front of us—it’s also about bearing witness to what might otherwise remain unseen. The camera isn’t just a tool—it’s a way to show what many can’t or won’t.

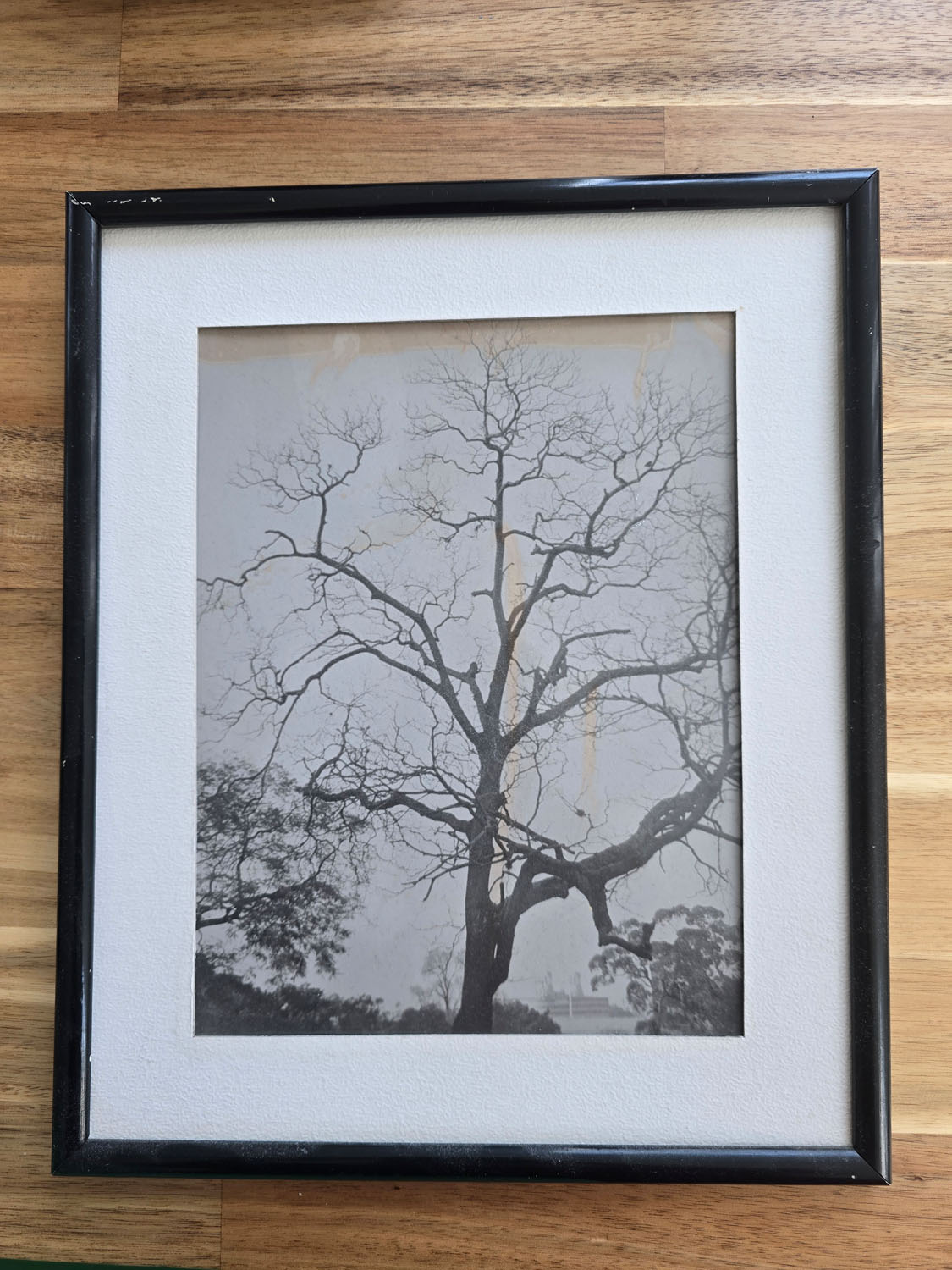

This was the first photo I ever took with my Olympus, developed by me during a photography course at ARGRA in Argentina.

Beyond photography, one of my hobbies is drawing. I mostly create what I call “enmantadas”—inspired by women, usually Muslim, who move me deeply. From that, I created my own merchandise line: pins, stickers, mugs, tote bags, keychains, and more.

Thank you for having me!

Juli.B

2. Teheran – Canon G16

2. Tehran – Canon EOS 3

2. Pakistan

Text and Photos by Juli Brigo